Commemorating Fiction: Passover Complications

This was originally published in the congregational newsletters of The Birmingham Temple and Kol Hadash Humanistic Congregation

Five hundred years ago, the meaning of the Passover holiday was relatively simple. The family would gather to retell the Biblical story of God’s intervention on the behalf of the people of Israel, delivering them from Egyptian slavery to “freedom” under the law of God.

Five hundred years ago, the meaning of the Passover holiday was relatively simple. The family would gather to retell the Biblical story of God’s intervention on the behalf of the people of Israel, delivering them from Egyptian slavery to “freedom” under the law of God.

There was no question that the event had really occurred; after all, the Bible and Jewish tradition said quite clearly that it had. The traditional Haggadah was the perfect companion to the traditional story, glorying in God’s wonders and mostly celebrating the downfall of the Egyptians – for every drop of wine removed for a plague, how many plagues on the Egyptians at the Red Sea were multiplied in rabbinic interpretation?

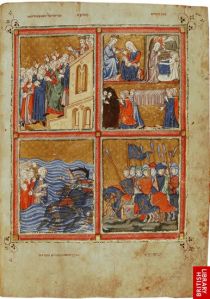

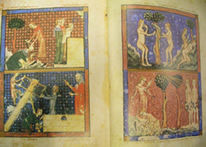

The rabbinic Passover ceremony went back many centuries for example, the four questions of the traditional Haggadah were largely written in the same form in the Mishnah, the first official collection of Rabbinic teachings, around 200 CE, and the original account of the Exodus story in the Biblical book of Exodus includes the instruction to tell the story to your children and to answer their questions (Exodus 12:26-27). Until the dawn of the modern period, different editions of the Haggadah varied in their decorations, never in their content or theology.

Both the Sarajevo Haggadah (left, c. 1350) and the Golden Haggadah (right, c. 1320) depict Biblical scenes in their own time and place!

Both the Sarajevo Haggadah (left, c. 1350) and the Golden Haggadah (right, c. 1320) depict Biblical scenes in their own time and place!

Modern developments have rendered the traditional Haggadah and the entire Passover celebration much more difficult to reconcile with our beliefs. These new intellectual trends force us to either change the ceremony, to ignore modern thought, or to embrace cognitive dissonance and do neither, believing one thing and saying another. Here are a few examples of the problems posed to us by modernity:

1) Historical study: There has been voluminous and vociferous debate among archaeologists and other academics on whether the Exodus ever happened, let alone when or how. One “middle-ground” position is that there may have been some sort of slave escape from Egypt, maybe even led by someone with the Egyptian name of Moses, but certainly not in the numbers and with the miracles of the Passover story. There is no archaeological evidence of that many people moving through the area, especially in any period close to when this event might have happened, and there is no mention of the Hebrews or plague-like disasters in Egyptian records from the same era. What happens when the story is undermined by historical investigation?

2) Humanistic/humanitarian sensitivity to non-Jews: Today, we don’t like to cheer the suffering of anyone, even the Egyptians. The common Egyptians suffer terribly for the stubbornness (possibly God-induced) of Pharaoh, an unelected dictator. Particularly heinous is the 10th plague, where innocent children are killed just to show God’s power, which had already been shown 9 times, “from Pharaoh on his throne to the prisoner in the dungeon.” (Exodus 12:29). If our adversaries are defeated today, we strive to sigh with relief rather than gloat and exult. How do we deal with the plagues in the story humanistically? Honestly, a removing a drop of wine while joking around with toy frogs and locusts is rather weak compensation. Perhaps the only silver lining is that it likely didn’t happen (see #1 above).

3) Feminism and Other Modern Values – In all traditional services, there are strong strains of patriarchy, and the Haggadah is no different. For example, there is the story of the four sons, but where are any daughters? The Exodus story claims 600,000 men left Egypt, but how many women and children? An interesting addition to some seders today has been an orange, the result of a story of Jewish feminism. The legend (not true) is that a traditional rabbi, asked about women becoming rabbis, replied, “A woman belongs on a bima [synagogue platform] like an orange belongs on a Seder plate.” It may well have begun as a message of LGBT inclusion that evolved into an orange. Whatever the origin, new symbols are very popular!

4) Humanistic Judaism: The most important issue that we face as Humanistic Jews is one of philosophy and theology. We do not believe in the active, supernatural, providential God of the Exodus story, and so we do not believe in either the factual truth of the story as told or the conventional lessons of piety and faith derived from it. Nor do we agree with the fundamental message of the traditional Haggadah when it answers the question ‘why is this night different from all other nights’: “Because we were slaves of Pharoah in Egypt, and God brought us from there with a mighty hand.” If you edit all of the blessings and thank-you’s and praises out of the Haggadah, is there enough left that is recognizable?

How can we solve these problems? Is Passover un-redeemable because of its supernaturalism and insensitivity? Of course not; the Jewish people wrote the story and the Haggadah in the first place, and we reserve the right to edit and add to it. Instead of discussing the joy of being miraculously liberated, we can emphasize the power of, to quote an early Zionist title, ‘Auto-emancipation.’ Instead of celebrating the suffering of the Egyptians, we commiserate with those who suffer, both from natural disasters and from the cruel behavior of others. We elicit sympathy for those still enslaved in many ways, both Jews and non-Jews; after all, as they say, ‘there but for the grace of God go we.’ Another coincidence of Jewish history is that the Warsaw Ghetto rebellion in 1943 began on the first night of Passover; this presents a wonderful opportunity to remember them, their courage, and their struggle for dignity. There are any number of changes we can make to make Passover relevant.

These are powerful additional themes we may add to or emphasize in the story, but what about that original story? Should we only tell what history permits, theorizing that perhaps a small band of proto-Hebrews escaped from Egypt and joined native Canaanite settlements, eventually evolving into Israel? Or can we simply tell the story as fiction, as the Greeks may have told their myths long after actual belief in them had faded?

We should do both. As a Humanistic Jewish child, I had little difficulty understanding that the account we heard during the Seder was a story and not history, especially since our humanistic Haggadah kept referring to it as ‘the story,’ not the event. Yet the deeper question remains: should we bother to tell the story at all? Telling the story has been part of Passover for 2500 years, but so has telling what you believe are the important meanings of Passover. Therefore we should continue the latter tradition by doing the former, and then adding in those elements which make the ceremony relevant and meaningful to our time and to us. There is never anything wrong with making a holiday more meaningful.